Inside A Xinjiang Detention Camp

December 03, 2020This account of the camp at Mongolküre in China’s Xinjiang region — known as Zhaosu in Chinese — provides an intimate, prisoner’s-eye view of a single complex purpose-built to detain and dehumanize the people held inside. Each detail reveals careful planning in the service of total control. The cells, classrooms, and hallways are wired with cameras and microphones. The slightest infractions, such as speaking their native language, can lead to violent retribution. Their government captors exert extreme authority over their every move. Detainees must sit up straight. They must bow their heads. They cannot even walk down a hallway without following painted lines along the floor. There’s no fresh air. Little stimulation. Only confinement.

The three former detainees all described being beaten over small infractions, such as speaking Kazakh. They faced interrogations as often as once a week, where they would be asked the same questions over and over again about why they had gone to Kazakhstan, whom they knew there, and what their personal religious beliefs were. They were forced to pledge loyalty to the Communist Party. Sometimes they were asked to write and sign “self-criticism” documents.

But what they remember most about their time in Xinjiang’s camps is the shame they felt for being treated like criminals — locked up for weeks without going outside — despite never being accused of a crime.

The three believe they were brought to the camp for having lived in Kazakhstan, which the Chinese government deems a sign of divided loyalties.

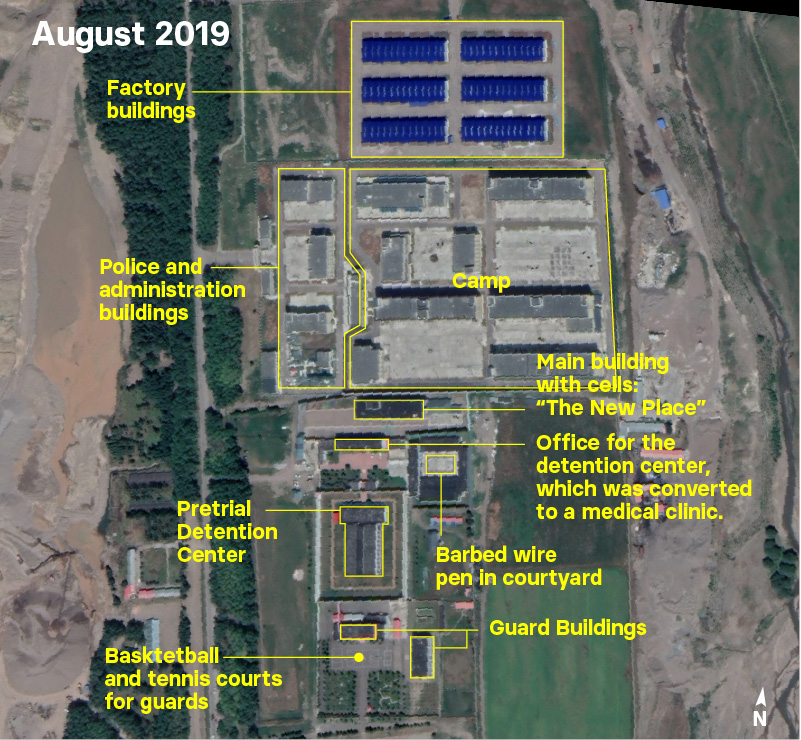

Satellite photos buttress their accounts with dramatic visual evidence — and document the Mongolküre camp’s mushrooming growth after they were released. High-resolution imagery shows details such as the barbed wire pens in the courtyard where detainees were occasionally brought to exercise, the passage leading from the guardhouse to the main accommodation building, the colors of the outside walls.

A barbed wire passageway led across the courtyard from the gated entrance to the large building where cells and classrooms were located.

The walls inside were white too, but the wall of the cell where Ulan stayed with nine other men was covered with the Chinese flag and a poster with the emblem of the Communist Party and the words to the national anthem. That made the room, which would normally house only three or four people, feel claustrophobic. There was also a “code of conduct” posted — beginning with the command that they must immediately jump out of bed when the wake-up call came in the morning, followed by other rules designed to control the minutiae of their daily lives in their cells.

The detainees were taken to exercise within the small open spaces inside the camps about once every few weeks, they remembered. After being inside for so long, it felt strange to see the sky above them.

O. noticed that the detainees wore different uniforms; he and others wore black, indicating they were not considered high-risk. Others wore yellow and red uniforms. Those in red were considered the most dangerous. O. was not sure what they might have done to land themselves in that category.

Inside the building where O. stayed, the hallways were marked with red and yellow lines, indicating where detainees were meant to walk in single file, usually with their heads down.

The rooms, which could house more than a dozen people, were about 14.1 feet long (4.3 meters) and 20 feet wide (6.1 meters), according to a BuzzFeed News architectural analysis — a little over half the size of a two-car garage. The detainees spent nearly all their time there, often as many as 23 hours a day.

…

Sometimes, Ulan thought, the food they brought them was warmed-over leftovers from the camp staffers’ lunches. Before meals, the detainees would be asked to stand and sing patriotic Chinese songs like “Socialism Is Good” and “Without the Communist Party, There Would Be No New China,” both popular during the Mao era.

During the days, the detainees were usually required to go to class for about an hour to study the Chinese language and political dogma, like the party slogan “love the Communist Party and love the country.” The overcrowding in the camp meant classroom time was limited. Classrooms, which were on the second and third floors of the building, had a thick transparent barrier between the students and the teacher.

Classes began with a patriotic song too. The three Kazakh men interviewed for this story were all fluent in Mandarin Chinese but were forced to study it anyway, making them wonder why they had been brought to the camp at all.

Each cell had a loudspeaker and an intercom, through which guards and camp officials would shout orders. When they ate meals or read books, prisoners had to sit perfectly upright on either plastic stools or the edge of their beds.

On one occasion, M. was beaten up with the butt of a gun, he said, after he’d broken a rule and was left covered with bruises.

A man the inmates called “Director Ma” was among those in charge of the camp, Ulan said. “He was a very cruel person.”

Guards watching the detainees through closed-circuit cameras — at least two in each cell — would monitor whether they were speaking their languages (for instance, Uighur or Kazakh) instead of Mandarin Chinese. One day in 2018, someone in Ulan’s room was found to be in violation.

“Director Ma came into our room, asked everyone to stand facing the window, and then called their names out one by one,” Ulan remembered.

Raising an electric baton, Ma beat them over their backs. Ulan remembers the screaming. “Their screams must have scared everyone in the building,” he said.

Ulan was last in line. He felt his body tense, waiting for the blow. But Ma paused, telling the detainees that if anyone dared to speak a language other than Chinese again, they would be sent to solitary confinement for a week.

Then Ma raised his arm and struck.