Inside Xinjiang: A 10-Day Tour of China’s Most Repressed State

January 24, 2019Twice a day, employees at an upscale jewelry boutique in China’s remote western region of Xinjiang stop what they’re doing and don bulletproof vests and combat helmets. Thrusting long clubs, they practice defending the store against attackers. Their imaginary assailants aren’t jewel thieves—they’re Muslim terrorists.

…

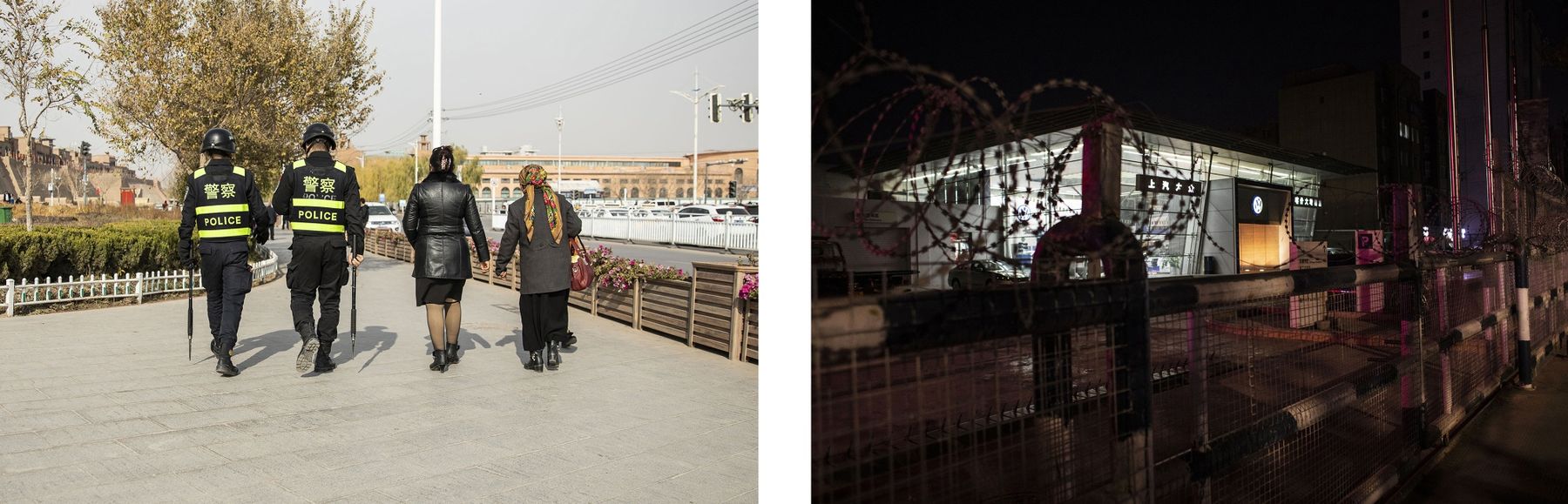

Police question them on the street, demanding to know where they’re going and why. Metal detectors, facial scanners and document checks are routine. Surveillance cameras are everywhere, even in some public restrooms. In one Uighur mosque, I counted 40 of them.

As I was riding in a packed third-class train car to Hotan, a former oasis town that once connected China to India, Uighur passengers fell silent and lowered their heads as a police officer walked in. Parents shushed their children. Soon, a dozen more men wearing blue train conductor suits and red armbands clambered in, pulling bags from the overhead racks and shouting commands. “Take this down!” “Open it!” “What’s this?” They took a young Uighur girl into the next car for questioning. A child started crying. When we arrived in Hotan, I approached a Uighur man and told him what had happened. “That’s what it’s been like every day for three years,” he said cautiously. Some of his family members had been sent to the Muslim camps, he added, where they spend all day studying Chinese law.

At one restaurant a waitress wore body armor, though it was unclear why: there is little visible crime in Khorgas. Police stations with flashing lights dotted the road and a near-constant whir of sirens filled the air.

Police patrolled the streets in teams of three, wielding shields and pointed black sticks. Soldiers marched with automatic weapons and sheathed bayonets. Wittingly or not, Han civilians play a part in the government’s efforts to stoke fears that a Uighur attack could happen at any moment. Groups of shopkeepers all around the city performed drills with wooden clubs. Knives were chained to the tables in butcher shops, and storefronts were barricaded at night. At times, the surveillance was excessive to the point of absurdity. Seven security officers were assigned to shadow me in Kashgar. When I asked a local police officer why such a large group was required, he denied the men were there at all. “You’re hallucinating,” he said.