The Factories In The Camps

December 28, 2020China has built more than 100 new facilities in Xinjiang where it can not only lock people up, but also force them to work in dedicated factory buildings right on site, BuzzFeed News can reveal based on government records, interviews, and hundreds of satellite images.

In August, BuzzFeed News uncovered hundreds of compounds in Xinjiang bearing the hallmarks of prisons or detention camps, many built during the last three years in a rapid escalation of China’s campaign against Muslim minorities including Uighurs, Kazakhs, and others. A new analysis shows that at least 135 of these compounds also hold factory buildings. Forced labor on a vast scale is almost certainly taking place inside facilities like these, according to researchers and interviews with former detainees.

Collectively, the factory facilities identified by BuzzFeed News cover more than 21 million square feet — nearly four times the size of the Mall of America. (Ford’s historic River Rouge Complex in Dearborn, Michigan, once the largest industrial complex in the world, is 16 million square feet.)

And they are growing in a way that mirrors the rapid expansion of the mass detention campaign, which has ensnared more than 1 million people since it began in 2016. Fourteen million square feet of new factories were built in 2018 alone.

Two former detainees told BuzzFeed News they had worked in factories while they were detained. One of them, Gulzira Auelhan, said she and other women traveled by bus to a factory where they would sew gloves. Asked if she was paid, she simply laughed.

The former detainees said they were never given a choice about working, and that they earned a pittance or no pay at all. “I felt like I was in hell,” Dina Nurdybai, who was detained in 2017 and 2018, told BuzzFeed News. Before her confinement, Nurdybai ran a small garment business. At a factory inside the internment camp where she was held, she said she worked in a cubicle that was locked from the outside, sewing pockets onto school uniforms. “They created this evil place and they destroyed my life,” she said.

She said she was paid a salary of 9 yuan — about $1.38 — in a month, far less than prevailing wages outside the walls of the detention camp.

It was a short walk to work — the distance from the residential buildings to the nearest factory was only 25 yards or so, while the farthest, on the opposite side of the site, was still just five minutes away. The women would work from 8 a.m. to noon, she said, and after lunch, again from 1:30 p.m. to 6:30 p.m. After the nine-hour day, they were required to take classes back in the building where they stayed, memorizing and repeating Chinese Communist Party propaganda and studying Mandarin Chinese.

The factory was equipped with new sewing machines, Nurdybai remembered. In fact, all the equipment inside looked new. But there were clues that those who worked there were not doing it by choice. Pairs of scissors were chained to each work table to prevent the women from taking them to the dorms, where they could, in theory, use them to harm themselves or stab the camp’s guards. And there were cameras everywhere, Nurdybai said, even in the bathrooms.

Inside the factory building, the floor was divided up, grid style, Nurdybai said. It was not like the factories that she had seen while running her own business. “There were cubicles at about chin height so you couldn’t see or talk to others. Each had a door, which locked,” she said, from the outside. Each cubicle had between 25 and 30 people, she said.

On one occasion, one of the camp staff justified the locked cubicles by saying, “These people are criminals, they can seriously harm you.” Police patrolled the floor of the factory.

Nurdybai ate with the other workers and slept in the same quarters as them. But, she said, her position as a trainer gave her one special privilege: She had a key fob with which she could open the doors to the bathroom. Others had to ask for permission to go.

Near the end of Nurdybai’s time in internment camps in September 2018, police officers finally told her what she was said to have done wrong: She had downloaded an illegal app called WhatsApp. She was later released and told her “education” was over. Her boyfriend at the time brought her a bouquet of flowers, as if she had just come home from a long trip.

But in the time she spent in the camps, her life had fallen apart. She owed a bank 70,000 yuan, or about $10,700, in business loans, on which she had been unable to make payments while she was detained.

Her clothing orders, too, had sat unfulfilled. “They took everything from my factory — expensive materials — they took it,” she said. “My customers, I had to pay them back.” She began selling off her possessions, even her car, to try and pay down the loan.

Factories started appearing in the makeshift camps of the early detention campaign in spring 2017. Often they appeared as a single factory wedged onto the site wherever there was room, squashed between the existing buildings, or built on the sports field of a former school. At the same time, new and expanding high-security facilities also added factories, typically in larger numbers.

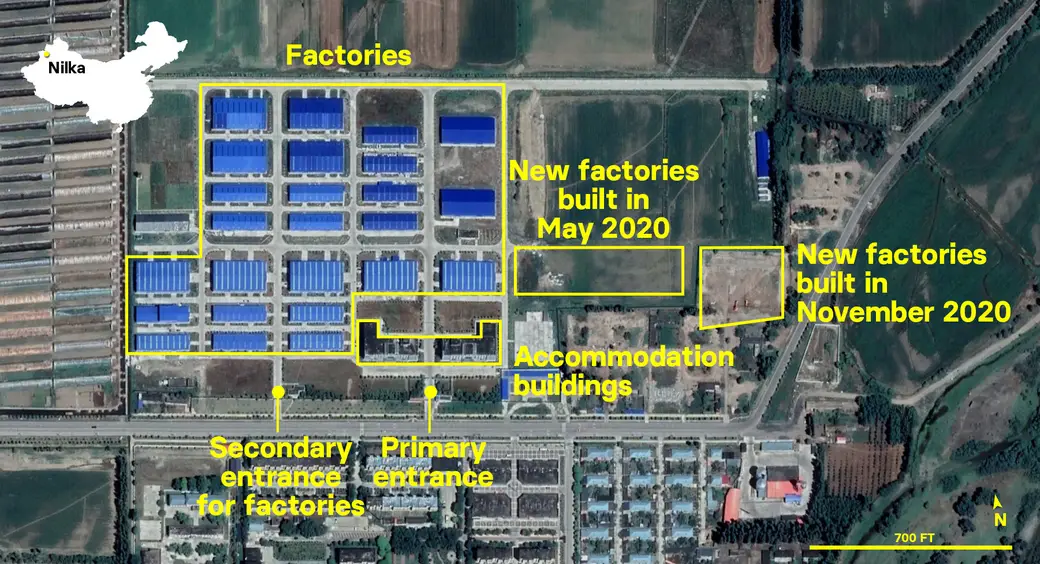

With the explosion of factory-building in 2018, new patterns emerged. The piecemeal addition of factory buildings on cramped existing sites continued. But the detention compounds on the edge of cities, which had more room, expanded to accommodate new factories that were typically arranged in a neat grid and often separated from the main compound — by a fence, or even a road with barbed wire walkways connecting the two. The factory area often had a separate entrance from the surrounding roads, allowing raw materials to be delivered and finished goods to be picked up without disturbing the wider camp.

While some of the new factories have been built in higher-security facilities, they are more often found in lower-security compounds, and they appear to be for light industry — manufacturing clothes rather than smelting zinc or mining. Much of the construction since 2017 has been concentrated in Xinjiang’s south and west: the regions with the highest numbers of Uighur and Kazakh people